Are camels the new cow of Kenya? This is probably not high on the list of questions you ask yourself during the course of a day. However, I ask myself this one question all the time. If you stick with me, you may find it a question worth considering.

I first started seriously thinking about camels in 2012 when a colleague asked if I would work with her on a project with Dromedary camels in Kenya. I immediately answered yes. This response was despite the fact that back in 2012 I knew roughly one thing about camels. Camels are incredibly cute!

In all fairness, I did know a few additional things about camels, having provided health care to these amazing creatures over the years. For example, I know some camels have one hump, the Dromedary camel, and some have two humps, the Bactrian camels. I also know that camels provide humans with a great many benefits. During fieldwork in Mongolia, I often saw Bactrian camels tied up to camel stands in front of apartment buildings in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar. These camels would wait patiently for their person(s) to come out so they could take them to their next stop. Camels are good beast of burden. They are also a major food source for millions of people across the globe. Today in the 21st Century, with many regions becoming hotter and drier, the role of camels is increasing. For example, in Kenya as climate change results in the conversion of semi-arid lands to more arid lands, many herders have switched to the drought resistant camel.

Camels in Kenya

When I think back to my PhD years working in Kenya in the 1990s, I do not recall seeing many camels during my studies. This is true even though the research was on tick borne diseases of livestock, and camels are livestock. Yet, I had no camels on my list of patients. If we fast-forward 25 years, the type of animals raised as food in Kenya has changed.

You may ask, “So what?”

The number of camels in Kenya has increased from an estimated 717,500 camels in 2000 to 2.9 million in 2013, and the number continues to grow. For comparison, during this same period the number of cattle declined by 25%. Camels in Kenya live across the landscape, often mingling with wildlife with whom they share the land.

Camels share more than just the land with these other species. They also share pathogens—disease causing infectious agents. This worries me. Camels may carry viruses, bacteria, and other pathogenic agents which may spill over and infect animals, both domestic species and wildlife, and humans.

The list of pathogens in camels is long and include infectious agents that cause well- known diseases such as trypanisomiasis, brucellosis and Q fever. If these three diseases aren’t enough to worry about, a new and growing concern is the camel associated Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV).

Camel zoonoses across the world

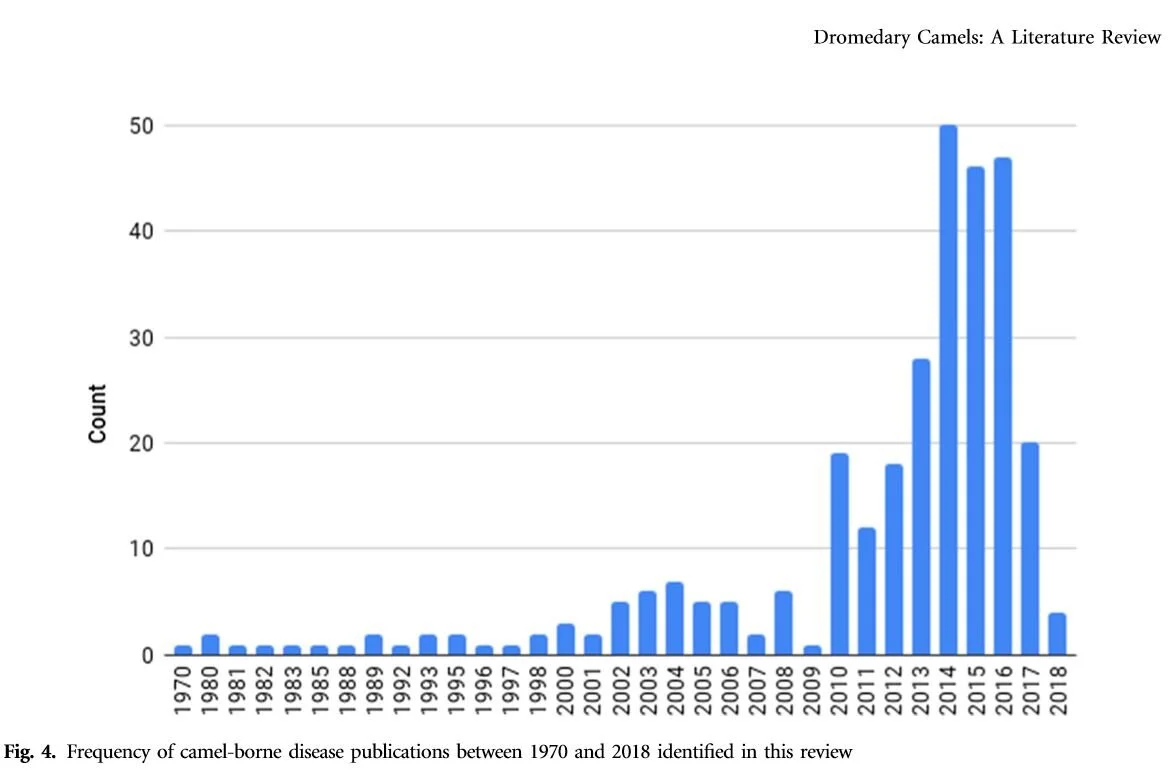

MERS, first detected in a person in 2012 in Jordan (the year I started to think about camels in a serious way!), is a threat to human health. In fact it was our finding evidence of camels exposed to this agent in Kenya (Deem et al., 2015) that led us to publish a review paper in 2019 covering the number of zoonotic pathogens (pathogens shared between human and non-human animals) across the globe that Dromedary camels may harbor (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-019-01413-7). MERS is on this list, but so are many other infectious diseases of public health concern. We also found the number of zoonotic disease events associated with Dromedary camels has increased significantly in recent years, starting around the time of the first diagnosed MERS human case.

In the seven years since I first went to Kenya to work with Dromedary camels, my respect for camels has only grown. They are amazing creatures. However, my concern for their welfare and for the health of the domestic livestock, wildlife, and humans with whom they have contact has also increased. In true One Health fashion, the story of Dromedary camels in Kenya includes many of the planetary challenges we face today. How do we provide protein and food security to a growing global human population—with 225,000 extra human mouths to feed a day—and at a time of significant climate change? How do we do this without causing irreversible harm to the other species that share the planet and the ecosystems that support all life?

We should all ask, Is the camel the new cow of Kenya? This one livestock species change in Kenya may have lasting negative impacts on wildlife conservation efforts there, and it may add to growing public health challenges in the region. This one change in one country with one species also represents one of the millions of seemingly small changes that may lead to big, global changes challenging the conservation of biodiversity and the protection of public health.

Answer = The camel is the new cow of Kenya!

Citations

Deem S.L., Fevre E.M., Kinnaird M., Browne S., Muloi D., Godeke G.-J., Koopmans M., Reusken C.B.E.M. 2015. Serological evidence of MERS-CoV antibodies in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Laikipia County, Kenya. PlosOne 10: e0140125. https://doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140125.

Browne, A.S., Fèvre, E.M., Kinnaird, M., Muloi, D.M., Wang, C.A., Larsen, P.S., O’Brien, T. and Deem, S.L. 2017. Serosurvey of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) in Dromedary Camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Laikipia County, Kenya. Zoonoses and Public Health. https://doi:10.1111/zph.12337.

Deem, S.L. 2018. Evaluating Camel Health in Kenya – An Example of Conservation Medicine in Action. In: Miller, R.E., P. Calle, and N. Lamberski (eds.), Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine: Volume 8. Saunders Elsevier, Saint Louis, Missouri. Pp 93- 98.

Zhu, S., Zimmerman, D., and Deem, S.L. 2019. A Review of Zoonotic Pathogens of Dromedary Camels. EcoHealth. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-019-01413-7.